Summary

This post justifies the claim that an identity system based on a permissioned distributed ledger is legitimately self-sovereign. The post also examines the claims to legitimacy that social login and distributed ledger identity systems make.

My last blog post was about creating an Internet for identity, a decentralized system that allows people and organizations to create identities independent of intervening administrative authorities. The post describes this system as self-sovereign and I call the system a self-sovereign identity system or SIS.

I believe the right way to construct SIS is using a public, permissioned distributed ledger. Permissioned ledgers have important properties that make them specifically useful for identity systems.

But permissioning implies governance. Someone has to determine who has permission to participate in approving transactions. If there are people making these kinds of decisions, how can a governed, permissioned ledger justify a claim that it supports self-sovereign identity?

John Locke and Sovereignty

John Locke was an English philosopher who had a big impact on the thinking of America’s founding fathers. Locke was concerned with power, who had it, how it was used, and how society is structured. More importantly, Locke’s theory of mind forms the foundation for our modern ideas about identity and independence.

Locke argued that “sovereign and independent” was man’s natural state and that we gave up freedom, our sovereignty, in exchange for something else, protection, sociality, commerce, among others. This grand bargain forms the basis for any society. As a community, the Internet proposes a similar bargain.

The goal of being self-sovereign isn't to be completely independent. With regard to the Internet: only machines without a network connection are completely independent. In the case of identity: only people without any relationships are completely independent. Seen from Locke's viewpoint, sovereignty is a resource each person combines with that of others to create society. Voluntarily giving up some of our rights to a state confers legitimacy on that state and its constitution.

Constitutional Orders and Legitimacy

Wikipedia defines legitimacy as

the right and acceptance of an authority, usually a governing law or a regime.

While this is most often applied to governments, I think we can rightly pose legitimacy questions for technical systems, especially those that have large impacts on people and society.

With respect to legitimacy, Philip Bobbit says:1

The defining characteristic ... of a constitutional order is its basis for legitimacy. The constitutional order of the industrial nation state, within which we currently live, promised: give us power and we will improve the material well-being of the nation.

In other words, legitimacy comes from the constitutional order: the structure of the governance. Citizens grant legitimacy to constitutional orders that meet their expectations by surrendering part of their sovereignty to them.

Regarding constitutional orders, Bobbitt says the following:2

The constitutional order of a state and its strategic posture toward other states together form the inner and outer membrane of a state. That membrane is secured by violence; without that security, a state ceases to exist. What is distinctive about the State is the requirement that the violence it deploys on its behalf must be legitimate; that is, it must be accepted within as a matter of law, and accepted without as an appropriate act of state sovereignty. Legitimacy must cloak the violence of the State, or the State ceases to be. Legitimacy, however, is a matter of history and thus is subject to change as new events emerge from the future and new understandings reinterpret the past.

Without legitimacy, the state cannot take action because neither it's citizens nor those on the outside who interact with it will see that action as authorized and thus it won't be accepted. Again, I believe these same principles can be applied to technical systems with broad societal impact. Without the support of it's users and the organizations rely on it, technical systems fail to be accepted.

My goal in this article is to apply these ideas about sovereignty, legitimacy, and constitutional orders to identity systems. Identity systems that seek to have large adoption and a broad spectrum of applications must have the support of a large class of users (analogous to citizens) and many relying parties (analogous to other states). They make promises that users and relying parties use to judge their legitimacy. Without legitimacy, they cannot succeed in their goals.

Social login, using your social media account to log into other sites, has become a popular means of reducing the identity management burden for users and relying parties alike. As I said earlier, my last post analyzed an emerging class of identity systems based on distributed ledger technology I called sovereign-identity systems (SIS). My thesis is that we are in the early stages of a change in the constitutional order for identity systems from social login to sovereign-identity systems. The rest of this article will focus on these two constitutional orders for identity systems, the promises they make, and their claims to legitimacy.

The Legitimacy of Social Login

Social media sites have become the largest providers of online identity through the use of social login. When you use Facebook to log into a third party Web site (known in identity circles as a relying party), you are participating in an identity regime that has a particular constitutional order and granting it legitimacy by your participation. Further, the relying party has also chosen to recognize the legitimacy of social login.

The constitutional order of social login is found in the terms and conditions in the contracts of adhesion that social login identity providers impose on people and relying parties alike. The system is a "take it or leave it" proposition with terms that can be changed at will by the social login identity provider.

A constitutional order makes different promises to those in the system (the users) and those on the outside (the relying parties). Let's examine the promise that social login makes:

To people social login says "use the identity we provide to you and we will make logging into sites you visit easy."

To relying parties, social login promises "use the identity we provide and trust us to accurately authenticate your users and we will reduce your costs, increase flexibility, and give you more accurate information about your users."

As successful as social login has been, there are a lot of places that social login has failed to penetrate. By and large, financial and health care institutions, for example, have not joined in to use social login. Why is this?

A constitutional theorist would say that they've failed the legitimacy test. Some relying parties and some people (either completely or for some use cases) have failed to yield their sovereignty to them. Legitimacy ultimately rests on trust that the regime can keep its promises. When that trust is missing or lost, the regime suffers a legitimacy crisis.

For people, the lack of trust in social login might be from fear of identity correlation, fear of what data will be shared, or lack of trust in the security of the social login platform.

For relying parties, the lack of trust may result from the perception that the identity provider performs insufficient identity proofing or the fear of outsourcing a critical security function (user authentication) to a third party. An additional concern is allowing a third party of have administrative authority for the relying party's users—not being in control of a critical piece of infrastructure. That is, they don't trust that the rules of the game might change arbitrarily based on the fluctuating business demands of the identity provider.3

These trust failings ultimately stem from the structure of the trust framework, the constitutional order, of social login. Because it's based on terms and conditions imposed by the identity provider whose primary business is something else, people and relying parties alike have less confidence in the future state of the identity system. So, it's good enough for some purposes, but not all.

The Legitimacy of Distributed Ledger Identity Systems

A distributed ledger identity system, what we've been calling SIS, has a different constitutional order. As we discussed in An Internet for Identity, nobody owns SIS, everybody can use it, and anyone can improve it. There are no identity providers. Anyone can create multiple identities on SIS to suit their needs. SIS is a public infrastructure for identity.

There's another important structural difference: SIS allows third party claim issuers to read and write claims about identifiers on the ledger. For example, the DMV (Department of Motor Vehicles) might write a claim about your authority to drive to the ledger. This claim would be sharable, by you, with others who are willing to trust the DMV. Anyone you share this claim with can verify that it came from the DMV and that it hasn't been tampered with.

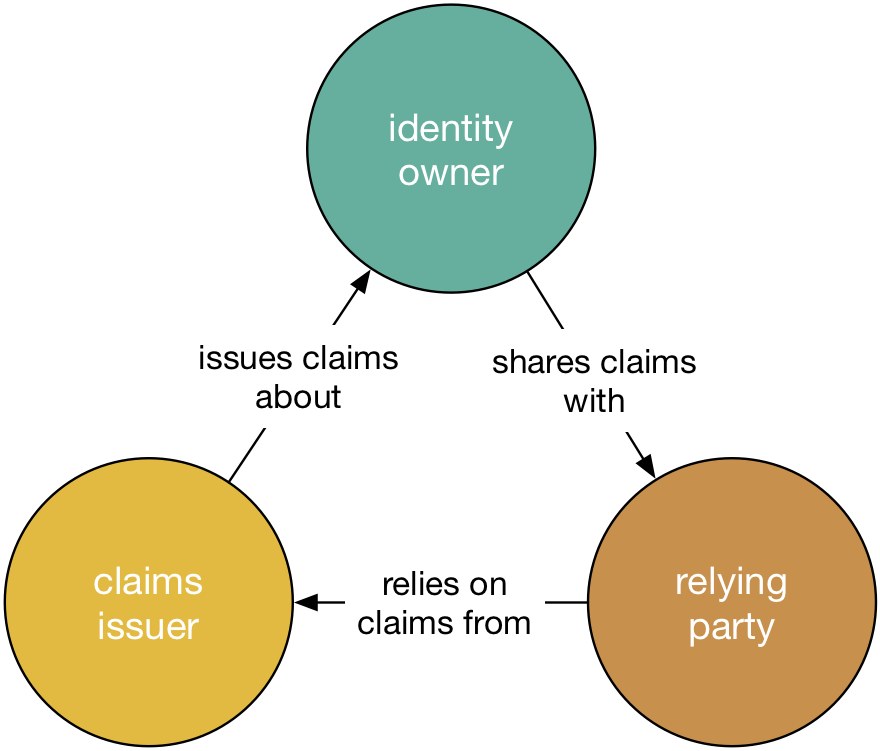

Claims issuers are distinguished from identity owners and relying parties.4 Their relationship with identity owners is that they issue claims about them. Relying parties rely on the claims that claims providers issues when they are shared by the identity owner. Allowing third party claim issuers to participate in the identity ecosystem opens up new and powerful opportunities for participants in an SIS ecosystem.

Because claim issuers and relying parties are distinguished, we will refer to them collectively as "other parties."

SIS makes the following promises:

To people: "Create as many identities as you like and use them how you see fit. You can keep them forever. We will ensure that you can use them privately and securely, sharing claims on those identities with other parties as you see fit."

To claim issuers: "Write claims about the identities with whom you have a relationship. We will ensure that your claims are secure and private (where appropriate)."

-

To relying parties: "Use claims made by yourself and others (when they are shared with you). We will ensure that these claims are secure and that you can trust them."

There are two ways we can presently realize SIS: with a permissionless ledger or a permissioned ledger. I'm going to assume that both of these are public, meaning anyone can use them. There are private, permissioned ledgers that are used within specific administrative domains. But SIS has to be public—everybody can use it—to meet the criteria of being like the Internet.

One factor in the constitutional order of permissionless and permissioned ledgers is who can validate (and thus, ultimately, write) to the ledger. While it's public and anyone can use it, the transactions have to be validated to prevent fraud.

In a permissionless system, anyone can be a validator. This leads to permissionless ledgers, like the Bitcoin blockchain, having to use some mechanism to ensure that validator voting is fair. Specifically, a permissionless ledger has to protect against Sybil attacks. If pseudonyms are cheap, cheaters can create as many a they like and use them in the validation process to vote for fraudulent transactions. Permissionless ledgers, therefore, use techniques like proof of work or proof of stake to increase the cost of participation and mitigate attacks.

Permissioned systems, on the other hand, control who can be a validator. Sybil attacks are not possible when the validators are known beforehand. But this creates a different problem: someone has to vet the validators and ensure that they are known and play by the rules. When a validator breaks the rules, there has to be a judicial process to review the issue and possibly ban the offending node from participating in future transaction validations. Consequently, we need a governance process to identify validators, set rules for their behavior, bind them to contracts, and adjudicate their behavior.

These different structures will affect how well these two different systems can meet the promises upon which an SIS stakes its legitimacy. While I don't believe it's necessarily a competition and that both kinds of ledgers will co-exist to meet different needs, I believe that permissioned ledgers have an edge in establishing trust with claim issuers and relying parties alike. A governance process allows a clear case to be made about trust and process.

In particular, we've seen instances in permissionless ledgers that led to blocks being orphaned or a smart contract being hacked. In both cases, code maintainers had to choose how to resolve the issue in the ledger. Their choice was a legitimacy problem because they had to convince the validators to move with them and support it. A permissioned system doesn't necessarily prevent these problems, but it can provide a clear, unambiguous judicial process for solving the problem. This provides clarity to everyone about what happens when something goes wrong. This is a clear advantage.

How will permissioned systems fare with people? That depends on the details of their constitutions. To the extent that governance is limited to controlling validators, and not limiting how identities are created and used in the system, people will see clear advantages in permissioned ledgers because they will attract claim issuers and relying parties that people want to interact with. Heavy-handed governance that limits individual control of identity, on the other hand, will turn people off and push them to permissionless systems where anything goes. This isn't binary, there's a spectrum of choices between these two extremes.

Surviving the Transition

In Bobbitt's theory of constitutional orders, transitions from one constitutional order to a new one always requires war. After all, since state constitutions represent a structure seeking legitimacy for its monopoly on violence, violence is necessarily the founding tenet of the state.

Technological systems aren't using their constitution in the same way. I believe one critical difference is that holding multiple citizenships in different online systems is entirely practical. Consequently, I believe people will continue to use social login alongside newer distributed-ledger identity systems for some time to come.

Claim issuers and relying parties might be another story. There very well could be a competition for other parties between different identity regimes and that is where I believe we'll see the benefits of these different constitutional orders being carefully weighed and hotly debated.

At least for some time, social login is going to win the "we have the most users" contest. But as we saw with Internet adoption, that didn't hold true very long for CompuServe, AOL, and Prodigy (among others). AOL was the only online service company to survive the transition. If SIS can fulfill its promise, the scales could tip swiftly as more and more claim issuers and relying parties see the benefit of SIS and adopt it, bringing their users with them.

Different Sovereign Identity Systems will have different constitutions. Not just whether they are permissionless or permissioned, but also within these broad classes. For example, there can be significant differences in the governance of permissioned ledgers. The most successful ones will be more like republics or democratic governments: they exert authority, but only that which is granted to them by the users, for the sake of the users.

-

Bobbitt, Philip. The Garments of Court and Palace: Machiavelli and the World That He Made (Kindle Locations 462-464).

Bobbitt, Philip. The Shield of Achilles: War, Peace, and the Course of History

-

Note that identity providers in the social login regime are not primarily in the business of providing identity. Their business is something else (mostly selling ads) and providing identity for social login is, from their perspective, part of serving that end.

-

Note that in practical usage, any given entity might play any of these three roles at different times.