Summary

Online services and interactions are being held back by the lack of identity systems that have the same virtues as the Internet. This post describes what we can expect from an Internet for identity.

In World of Ends, Doc Searls and Dave Weinberger enumerate the Internet's three virtues:

- No one owns it.

- Everyone can use it.

- Anyone can improve it.

If we wanted to build an identity system that was like the Internet, we'd want it to have those same virtues. To make the discussion below easier, let's call that system SIS (for sovereign identity system).

No One Owns It

Every online identity you have was given to you by someone else.

This simple fact makes every online identity completely different from identity in the physical world where you exist first, independently, as a sovereign human being.

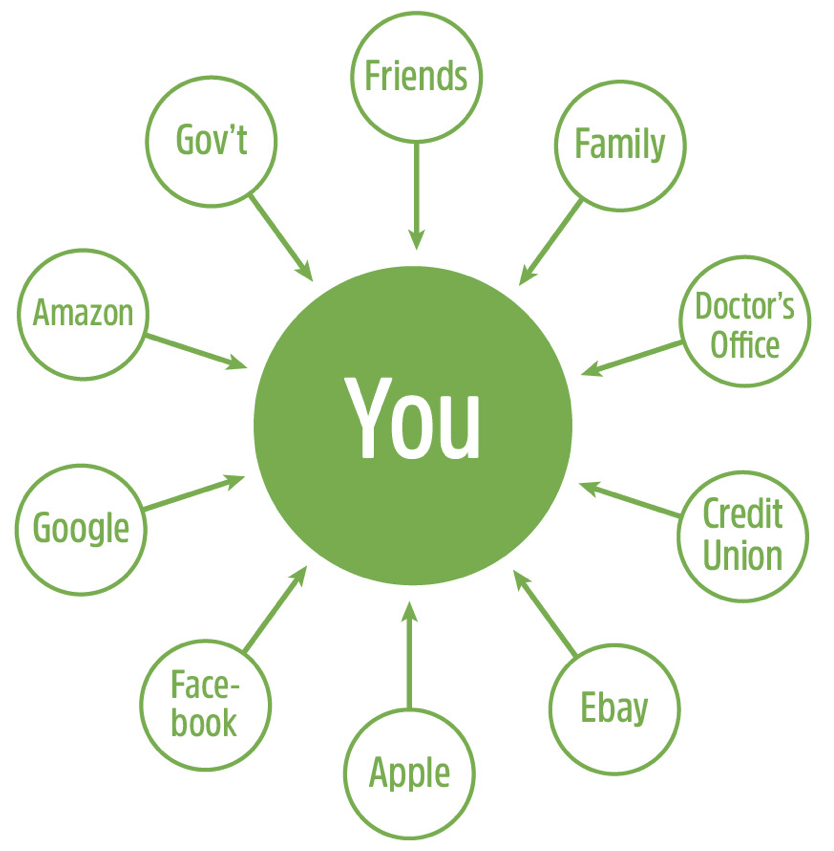

As a result, online relationships are skewed. There's an imbalance of power between people and organizations online. Here's why. Online identity looks like this:

To do business with Amazon, you have to create an account. So do I. We both get a relationship with Amazon based on an identity that we create within Amazon's namespace. That identity is subject to the (mostly unread) Terms and Conditions that Amazon places on the use of its service. Your use of the account is subject to whatever restrictions Amazon chooses to place on it. These can be changed retroactively. Furthermore, Amazon can take the account away at any time and you have very little recourse. Clearly Amazon owns the account and is letting you use it so long as such use suits their goals.

Of course, Amazon isn't unique here. This is how identity works online. Everyone knows that. For identity to be different, we'd need a way for people to create online identities that they control.

Such an identity system could turn this diagram inside-out, resulting in a picture where you are at the center:

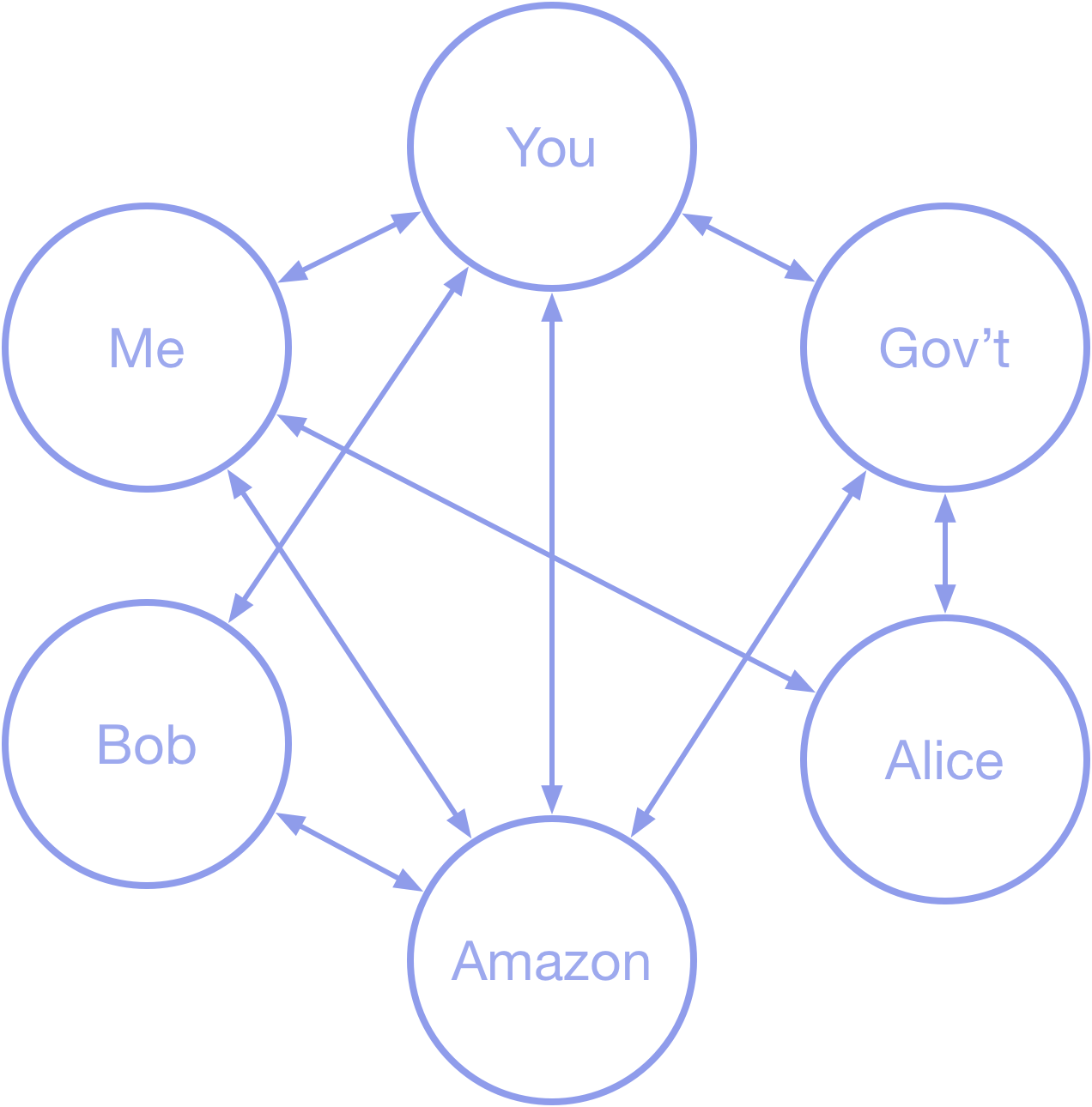

In SIS, individuals, businesses, and other organizations establish identities that exist independently of the other identities in the system. Those identities are peers. Of course, being at the center is perception. The reality looks more like the Internet:

Everyone Can Use It

Every online identity you have is subject to someone else granting you permission.

Anyone can use the Internet. No one has to give you permission. And no one can cut you off. You do need to get an IP address, but that's not a significant burden—they're widely available from multiple sources (and IPv6 was created to reduce that even further). Once you and I have an address, we can exchange IP packets to our heart's content. If your ISP cuts you off, you get another because they're substitutable, give me your new address, and we're back to exchanging packets.

An Internet-like identity system like SIS would be public. Anyone should be able to use it without getting permission from a system administrator or having to agree to terms and conditions that are changed arbitrarily or controlled and adjudicated by a closed process without recourse. An Internet-like identity system should be built so that everyone can participate on equal footing.

Anyone Can Improve It

You can only improve identity systems in ways their owners allow.

The Internet gets improved by lots of people everyday—most of whom have no formal relationship with the Internet's governance bodies. This happens in a couple of ways:

First, there is an open process for improving the system. On the Internet that happens through open protocols and open source code. This isn't a free-for-all. There are governance processes that control how these improvements are vetted and incorporated.

Second, anyone can design and build a new service on top of these protocols. DNS, email, and other services are all built on top of the Internet. So are the World Wide Web and things like Amazon, Facebook, and Google.

An Internet-like identity system should allow these same kinds of improvements. While governance is necessary, that doesn't diminish the virtues of the open platform. One of the paradoxes of decentralized platforms is that they require more formal governance than centralized ones.

Because its public, anyone can use SIS for anything it's protocols allow. That freedom gives rise to innovation. I fully expect that SIS would be used for purposes and in ways that it's designers could never imagine—just like the Internet.

Properties

As I wrote in The CompuServe of Things, the Internet works because it's (1) decentralized, (2) heterarchical, and (3) interoperable. These properties and others follow from the virtues we've discussed above.

Decentralized—decentralization follows directly from the fact that no one owns it. This is the primary criterion for judging the degree of decentralization in a system. And as I mention above, not only can a system be decentralized and governed, some level of governance is necessary for decentralized systems to function well.

Heterarchical—a heterarchy is a "system of organization where the elements of the organization are unranked (non-hierarchical) or where they possess the potential to be ranked a number of different ways." The diagram in Figure 3 (above) shows identities in relationships with each other as peers. This is a heterarchy; there is no inherent ranking of nodes in the architecture of the system.

Interoperable—regardless of what providers or systems we use to connect to SIS, we should be able to interact with any other principles who are using it. We don't have to worry that our identity will only work on some specific provider's systems. And given that it's based on open protocols and software, other identity systems should be able to interoperate with it as well.

Substitutable—SIS is a protocol, an agreement if you will, about how systems that use it must behave to achieve interoperability. That means that anyone who understands the protocol can write software that uses SIS. The end result is that while there will likely be software, systems, and companies who provide access to and services on SIS, your identity and your use of it don't depend on any one of them. There are usable substitutes that provide choice and freedom.

Reliable—people, businesses, and others must be able to use it without worrying that it will go down, stop working, go up in price, or get taken over by someone who would do it and those who use it harm. This is larger than mere technical trust that a system will be available. It extends to the business model (or lack thereof) and the governance—the full BLT (business, legal and technical) stack.

Non-proprietary—no one has the power to change SIS by fiat or take away a person's identity. Further, it can't go out of business and stop operation because its maintenance and operation are distributed instead of being centralized in the hands of a single organization. Because SIS is more of an agreement than a technology or system, so long as those using it agree to work together according to its principles, it will continue to work—just like the Internet

Frequently Asked Questions

- Is SIS an identity provider? No. There are no identity providers in the way we've come to think of them. The whole notion of providing and identity to someone is based in the administrative identity realm.

- Why would businesses use SIS? Most businesses see their identity systems as a cost center, not a profit center. And yet they're reluctant to turn over access to their system to some other entity who may turn into a competitor someday. SIS solves this problem by providing an identity system that the business doesn't have to maintain and is non-proprietary. This is a big win for businesses across the Internet because it reduces friction and cost at the same time.

- Does this mean that businesses won't have their own accounts? The existence of SIS doesn't mean that businesses don't still have a need to keep track of their customers, record preferences, etc. Take Amazon as an example. While SIS could be used to provide credit card and address information to Amazon, They'd still want to know who their customers are and provide wish lists, shopping carts, and so on. Amazon might choose to store Amazon identity information about a person on SIS.

- What would SIS be used for? The short answer is that people and organizations would write claims on SIS about identities in the system. These claims might be public, public and verifiable, encrypted, jointly owned, or self-asserted. Identity owners could make use of these claims in a variety of ways. For example, my bank might write a claim that I control a particular credit card on SIS—encrypted, of course. I could then provide that validated credit card information to others when I needed to make a payment. In some ways it feels like 1Password, Keypass, or iCloud Keychain, but on a much grander scale and far more flexible.

- How could SIS be built? A few years ago, SIS was a dream people had, but without a clear technical path to achieving it. The introduction of blockchain technology changed that. Over the last few years, research in distributed ledger technology has exploded and SIS is now not only possible, but versions of it are being conceived and built by several organizations. I prefer a permissioned distributed ledger over permissionless for SIS.

An Internet for Identity

The Internet was created without any way for people, organizations, and other entities to be identified. On the Internet, only machines get identities in the form of IP numbers. This is understandable given what the creators of the Internet were trying to achieve. But the lack of a decentralized, heterarchical, and interoperable identity system has created an environment where the services most people use online are a lot more centralized than the Internet they exist upon.

We're finally at a point where that failing can be rectified. Multiple players are working on sovereign identity systems that use distributed ledgers to create identity systems that are owned by no one, can be used by everyone, and can be improved by anyone. These systems will result in increased flexibility for people, businesses, and others as well as enabling new innovations in online services.

Credits

Thanks to Timothy Ruff of Evernym for the big dot/little dot figures.