Summary

Verifiable credentials have a number of use cases in healthcare. Using them can reduce the administrative burden that people experience at the hands of the bureaucracies that inevitably develop.

I have a medical condition that requires that I get blood tests every three months. And, having recently changed jobs, my insurance, and thus the set of acceptable labs, changed recently. I know that this specific problem is very US-centric, but bear with me, I think the problems that I'll describe, and the architectures that lead to them, are more general than my specific situation.

My doctor sees me every 6 months, and so gives me two lab orders each time. Last week, I showed up at Revere Health's lab. They were happy to take my insurance, but not the lab order. They needed a date on it. So, I called my doctor and they said they'd fax over an order to the lab. We tried that three times but the lab never got it. So my doctor emailed it to me. The lab wouldn't take the electronic lab order from my phone, wouldn't let me email it to them (citing privacy issues with non-secure email), and couldn't let me print it there. I ended up driving to the UPS Store to print it, then return to the lab. Ugh.

This story is a perfect illustration of what David Graeber calls the Utopia of Rules. Designers of administrative systems do the imaginative work of defining processes, policies, and rules. But, as I wrote in Authentic Digital Relationships:

Because of the systematic imbalance of power that administrative ... systems create, administrators can afford to be lazy. To the administrator, everyone is structurally the same, being fit into the same schema. This is efficient because they can afford to ignore all the qualities that make people unique and concentrate on just their business. Meanwhile subjects are left to perform the "interpretive labor," as Graeber calls it, of understanding the system, what it allows or doesn't, and how it can be bent to accomplish their goals. Subjects have few tools for managing these relationships because each one is a little different from the others, not only technically, but procedurally as well. There is no common protocol or user experience [from one administrative system to the next].

The lab order format my doctor gave me was accepted just fine at Intermountain Health Care's labs. But Revere Health had different rules. I was forced to adapt to their rules, being subject to their administration.

Bureaucracies are often made functional by the people at the front line making exceptions or cutting corners. In my case no exceptions were made. They were polite, but ultimately uncaring and felt no responsibility to help me solve the problem. This is an example of the "interpretive labor" borne by the subjects of any administrative system.

Centralizing the system—such as having one national healthcare system—could solve my problem because the format for the order and the communication between entities could be streamlined. You can also solve the problem by defining cross-organization schema and protocols. My choice, as you might guess, would be a solution based on verifiable credentials—whether or not the healthcare system is centralized. Verifiable credentials offer a few benefits:

- Verifiable credentials can solve the communication problem so that everyone in the system gets authentic data.

- Because the credentials issued to me, I can be a trustworthy conduit between the doctor and the lab.

- Verifiable credentials allow an interoperable solution with several vendors.

- The tools, software, and techniques for verifiable credentials are well understood.

Verifiable credentials don't solve the problem of the lab being able to understand the doctor's order or the order having all the right data. That is a governance problem outside the realm of technology. But because we've narrowed the problem to defining the schema for a given localized set of doctors, labs, pharmacies, and other health-care providers, it might be tractable.

Verifiable credentials are a no-brainer for solving problems in health care. Interestingly, many health care use cases already use the patient as the conduit for transferring data between providers. But they are stuck in a paper world because many of the solutions that have been proposed for solving it, lead to central systems that require near-universal buy-in to work. Protocol-based solutions are the antedote to that and, fortunately, they're available now.

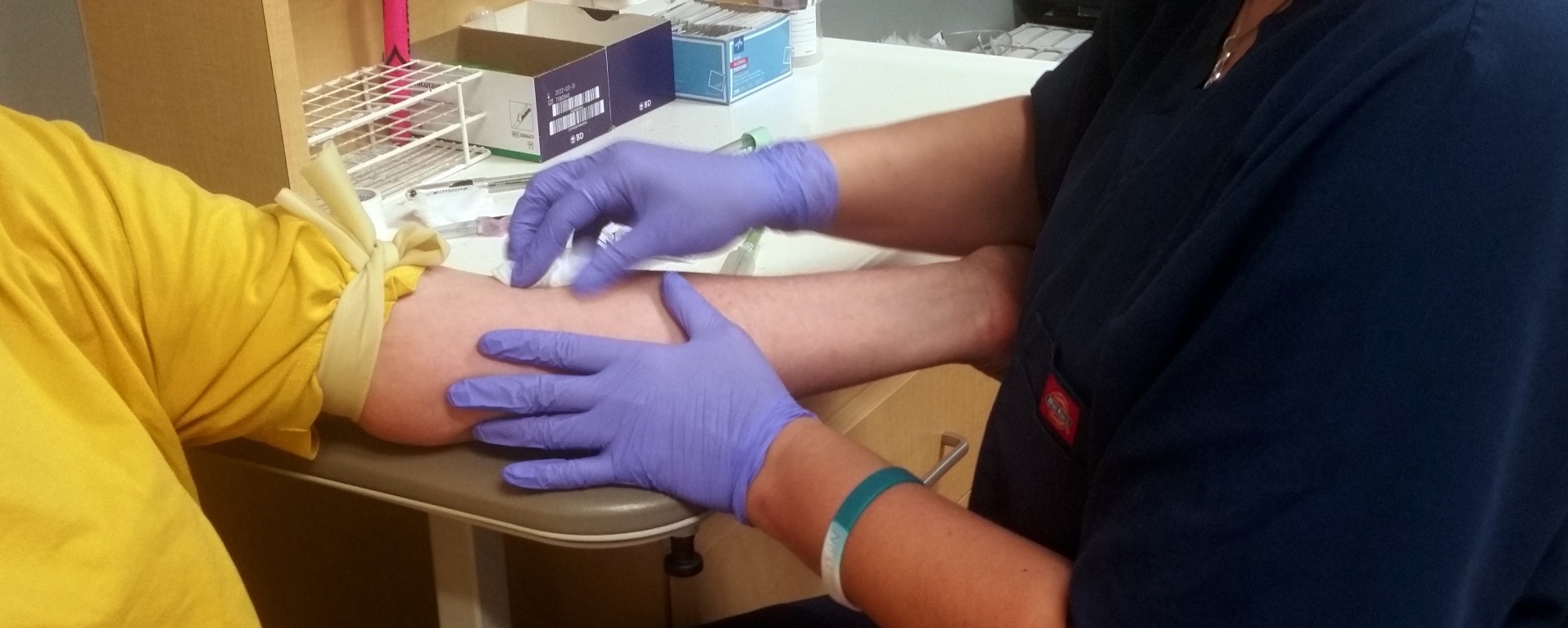

Photo Credit: Blood Draw from Linnaea Mallette (CC0 1.0)