Summary

Authenticity and privacy are usually traded off against each other. The tradeoff is a tricky one that can lead to the over collection of data.

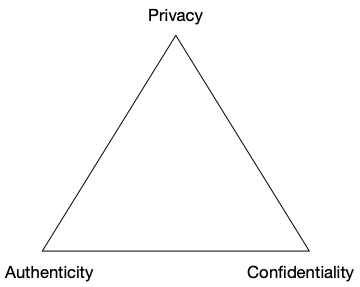

At a recent Utah SSI Meetup, Sam Smith discussed the tradeoff between privacy, authenticity and confidentiality. Authenticity allows parties to a conversation to know to whom they are talking. Confidentiality ensures that the content of the conversation is protected from others. These three create a tradespace because you can't achieve all three at the same time. Since confidentiality is easily achieved through encryption, we're almost always trading off privacy and authenticity. The following diagram illustrates these tradeoffs.

Authenticity is difficult to achieve in concert with privacy because it affects the metadata of a conversation. Often it requires others besides the parties to a conversation potentially knowing who else is participating—that is, it requires non-repudiation. Specifically, if Alice and Bob are communicating, not only does Alice need to know she's talking to Bob, but also needs the ability to prove to others that she and Bob were communicating.

As an example, modern banking laws include a provision known as Know Your Customer (KYC). KYC requires that banks be able to identify the parties to transactions. That's why, when you open a bank account, they ask for numerous identity documents. The purpose is to enable law enforcement to determine the actors behind transactions deemed illegal (hopefully with a warrant). So, banking transactions are strong on authenticity, but weak on privacy1.

Authenticity is another way of classifying digital relationships. Many of the relationships we have are (or could be) ephemeral, relying more on what you have than who you are. For example, a movie ticket doesn't identify who you are but does identify what you are: one of N people allowed to occupy a seat in a specific theater at a specific time. You establish an ephemeral relationship with the ticket taker, she determines that your ticket is valid, and you're admitted to the theater. This relationship, unless the ticket taker knows you, is strong on privacy, weak on authenticity, and doesn't need much confidentiality either.

A credit card transaction is another interesting case that shows the complicated nature of privacy and authenticity in many relationships. To the merchant, a credit card says something about you, what you are (i.e., someone with sufficient credit to make a purchase) rather than who you are—strong on privacy, relatively weak on authenticity. To be sure, the merchant does have a permanent identifier for you (the card number) but is unlikely to be asked to use it outside the transaction.

But, because of KYC, you are well known to your bank, and the rules of the credit card network ensure that you can be identified by transaction for things like chargebacks and requests from law enforcement. So, this relationship has strong authenticity but weaker privacy guarantees.

The tradeoff between privacy and authenticity is informed by the Law of Justifiable Parties (see Kim Cameron's Laws of Identity) that says disclosures should be made only to entities who have a need to know. Justifiable Parties doesn't say everything should be maximally private. But it does say that we need to carefully consider our justification for increasing authenticity at the expense of privacy. Too often, digital systems opt for knowing who when they could get by with what. In the language we're developing here, they create authenticated, permanent relationships, at the expense of privacy, when they could use pseudonymous, ephemeral relationships and preserve privacy.

Trust is often given as the reason for trading privacy for authenticity. This is the result of a mistaken understanding of trust. What many interactions really need is confidence in the data being exchanged. As an example, consider how we ensure a patron at a bar is old enough to drink. We could create a registry and have everyone who wants to drink register with the bar, providing several identifying documents, including birthdate. Every time you order, you'd authenticate, proving you're the person who established the account and allowing the bar to prove who ordered what when. This system relies on who you are.

But this isn't how we do it. Instead, your relationship with the bar is ephemeral. To prove you're old enough to drink you show the bartender or server an ID card that includes your birthday. They don't record any of the information on the ID card, but rather use the birthday to establish what you are: a person old enough to drink. This system favors privacy over authenticity.

The bar use case doesn't require trust, the willingness to rely on someone else to perform actions on the trustor's behalf, in the ID card holder2. But it does require confidence in the data. The bar needs to be confident that the person drinking is over the legal age. Both systems provide that confidence, but one protects privacy, and the other does not. Systems that need trust generally need more authenticity and thus have less privacy.

In general, authenticity is needed in a digital relationship when there is a need for legal recourse and accountability. Different applications will judge the risk inherent in a relationship differently and hence have different tradeoffs between privacy and authenticity. I say this with some reticence since I know in many organizations, the risk managers are incredibly influential with business leaders and will push for accountability where it might not really be needed, just to be safe. I hope identity professionals can provide cover for privacy and the arguments for why confidence is often all that is needed.

Notes

- Remember, this doesn't mean that banking transactions are public, but that others besides the participants can know who participated in the conversation.

- The bar does need to trust the issuer of the ID card. That is a different discussion.

Photo Credit: Who's Who in New Zealand 228 from Schwede66 (CC BY-SA 4.0)