Summary

I read a couple of interesting things the past few weeks that have me thinking about the world we're building, the impact that tech has on it, and how it self-governs (or not).

In The crypto-communists behind the Web3 revolution, Benjamin Pimentel argues that "The future of decentralized finance echoes a decidedly Marxist vision of the future." He references various Silicon Valley icons like Jack Dorsey, Marc Andreessen, Elon Musk, and others, comparing their statements on Web3 and crypto with the ideology of communism. He references Tom Goldberg's essay exploring the similarities between Karl Marx and Nakamoto Satoshi:

"Marx advocated for a stateless system, where the worker controlled the means of production," [Goldberg] said. "Satoshi sought to remove financial intermediaries — the banks and credit card companies that controlled the world's flow of value."

But while Marx and Satoshi both "articulated a reasoned, well-thought-out vision of the future," Goldenberg added, "neither had the power to predict how their ideas would influence others or be implemented. And neither could control their own creations."

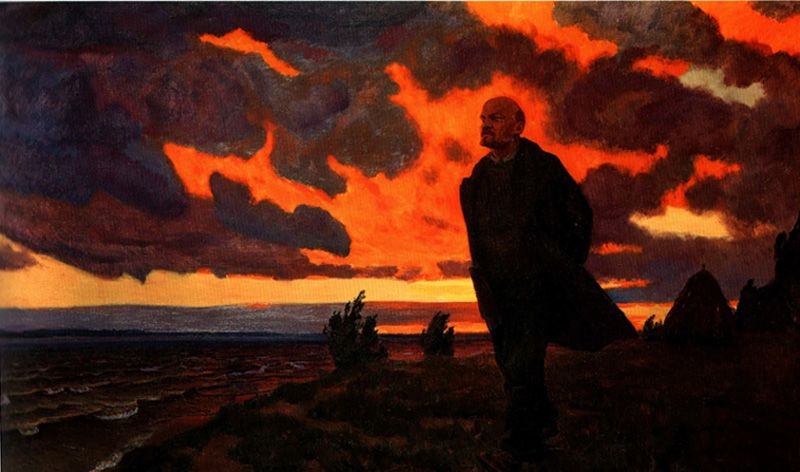

And, among other things, compares Musk to Lenin:

But Musk and Lenin seem simpatico when it comes to the "ultimate aim of abolishing the state" (Lenin): "Just delete them all," Musk recently said, of the government subsidies that have historically sustained his firms. (Perhaps he's studied Mao Zedong's essay "On Contradiction.")

"So long as the state exists there is no freedom," Lenin declared. "When there is freedom, there will be no state."

All in all, it's an interesting read with lots to think about. But what really made it speak to me is that I've also been reading The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty by Benjamin Bratton, the Director of the Center for Design and Geopolitics at the University of California, San Diego. I won't lie; the book is, for a non-sociologist like me, a tough read. Still, I keep going cause there are so many interesting ideas in it.

Relevant to the crypto-communist article is the idea of platform sovereignty. Bratton references Carl Schmitt's arguments on the relationship between political epochs and spatial subdivision. As Bratton says there is "no stable geopolitical order without an underlying architecture of spatial subdivision" and "no geography without first topology."

Here's his insight on the heterarchical relationship between markets and states

[O]ne of the things that makes neoliberalism unique is that markets do not operate in conjunction with or in conflict with sovereign states, but rather that sovereignty is itself shifted from states into markets.

The point here is that markets and states co-exist, influencing each other. And that sovereignty can shift. Both are ways of creating coherence among participants. I think that's a good way to explore what Bratton means when he talks about platform sovereignty.

One of the important ideas in The Stack is that platforms rarely replace each other. Rather, they co-exist, strengthening or diminishing other platforms. Market's didn't do away with states—even as they stole attention and power from them. And, the internet didn't do away with either. The degree of sovereignty these platforms and their Users (in Bratton's terminology) enjoy depends on a variety of factors, but it most assuredly doesn't rely wholly on permission from other platforms.

In this worldview, there are innumerable platforms, not nicely contained within each other, but stacked willy-nilly with overlapping boundaries. Schmitt was primarily interested in geopolitical boundaries that played out in the Westphalian regime1. Bratton recognizes that one thing networks have given us is lots of boundaries, each one giving rise to sovereignty of various forms and in different degrees.

While many focus on what Doc Searls calls "vendor sports" and talk about which platform triumphs over another, Bratton's view is that when you stop looking at platforms in a specific type or category, there's not necessarily competition, and less so, the means of control between them that would ensure the ascendance and triumph of one over the other. Each is a social system with its own participants, rules, and goals.

Social systems that are enduring, scalable, and generative require coherence among participants. Coherence allows us to manage complexity. Coherence is necessary for any group of people to cooperate. The coherence necessary to create the internet came in part from standards, but more from the actions of people who created organizations, established those standards, ran services, and set up exchange points.

Coherence enables a group of people to operate with one mind about some set of ideas, processes, and outcomes. We only know of a few ways of creating coherence in social systems: tribes, institutions, markets, and networks2. Startups, for example, work as tribes. When there's only a small set of people, a strong leader can clearly communicate ideas and put incentives—and disincentives—in place. Coherence is the result. As companies grow, they become institutions that rely on rules and bureaucracy to establish coherence. While a strong leader is important, institutions are more about the organization than the personalities involved. Tribes and institutions are centralized--someone or some organization is making it all happen. More to the point, institutions rely on hierarchy to achieve coherence.

Markets are decentralized—specifically they are heterarchical rather than hierarchical. A set of rules, perhaps evolved over time through countless interactions, govern interactions and market participants are incented by market forces driven by economic opportunity to abide by the rules. Competition among private interests (hopefully behaving fairly and freely) allows multiple players with their own agendas to process complex transactions around a diverse set of interests.

Networks are also decentralized. Most of the platforms we see emerging today are networks of some kind. The rules of interaction in networked platforms are set in protocol. But protocol alone is not enough. Defining a protocol doesn't string cable or set up routers. There's something more to it.

As we've said, one form of organization doesn't usually supplant the previous, but augments it. The internet is the result of a mix of institutional, market-driven, and network-enabled forces. The internet has endured and functions because these forces, whether by design or luck, are sufficient to create the coherence necessary to turn the idea of a global, public decentralized communications system into a real network that routes packets from place to place. The same can be said for any other enduring platform.

Funny, it was Marc Andreessen, one of Pimentel's crypto-communists, who introduced me to Neal Stephenson's Snow Crash in 1999. Snow Crash is set in a world where various network platforms co-exist with much-diminished nation states, a metaverse, and each other, molding the geopolitical landscape of the novel to the extent they engender coherence in their various Users.

So, while Pimentel's article is interesting and informative in comparing the stated aspirations of crypto-enthusiasts and communists, I think the more correct view is that crypto isn't going to replace anything—we're not headed to a crypto-communist future. Rather it's going to add more platforms that influence, but don't displace, the things that came before. And those who see Web3 as a passing fad will likely be disappointed that it refuses to die—so long it generates networked platforms that creates sufficient coherence among their Users.

Books Mentioned

The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty by Benjamin H. Bratton

A comprehensive political and design theory of planetary-scale computation proposing that The Stack—an accidental megastructure—is both a technological apparatus and a model for a new geopolitical architecture. What has planetary-scale computation done to our geopolitical realities? It takes different forms at different scales—from energy and mineral sourcing and subterranean cloud infrastructure to urban software and massive universal addressing systems; from interfaces drawn by the augmentation of the hand and eye to users identified by self—quantification and the arrival of legions of sensors, algorithms, and robots. Together, how do these distort and deform modern political geographies and produce new territories in their own image?

Snow Crash by Neal Stephenson

In reality, Hiro Protagonist delivers pizza for Uncle Enzo’s CosoNostra Pizza Inc., but in the Metaverse he’s a warrior prince. Plunging headlong into the enigma of a new computer virus that’s striking down hackers everywhere, he races along the neon-lit streets on a search-and-destroy mission for the shadowy virtual villain threatening to bring about infocalypse. • In this mind-altering romp—where the term "Metaverse" was first coined—you'll experience a future America so bizarre, so outrageous, you'll recognize it immediately • One of Time's 100 best English-language novels.

The Shield of Achilles: War, Peace, and the Course of History by Philip Bobbitt

For five centuries, the State has evolved according to epoch-making cycles of war and peace. But now our world has changed irrevocably. What faces us in this era of fear and uncertainty? How do we protect ourselves against war machines that can penetrate the defenses of any state? Visionary and prophetic, The Shield of Achilles looks back at history, at the “Long War” of 1914-1990, and at the future: the death of the nation-state and the birth of a new kind of conflict without precedent.

Notes

- For a deep dive into Westphalean "princely states" and their evolution into modern nation states, I can't recommend strongly enough Philip Bobbit's The Shield of Achilles: War, Peace, and the Course of History.

- To explore this more, see this John Robb commentary on David Ronfeldt's Rand Corporation paper "Tribes, Institutions, Markets, Networks" (PDF).

Photo Credit: Lenin from Arkady Rylov via Wikimedia Commons (CC0)