Summary

Much has been made of data lately. And with good reason. Data and the ability to exchange and process it are at the heart of modern society's productivity and prosperity. Data and algorithms are the engines that drive the economy in the 21st century. But data is often onerous to obtain, difficult to trust, and hard to understand. Fixing these problems--making trustworthy, understandable data flow more freely, consistently, and reliably--will provide a wellspring of new ideas and companies to prosecute them.

Much has been made of data lately. And with good reason. Data and the ability to exchange and process it are at the heart of modern society's productivity and prosperity. Data and algorithms are the engines that drive the economy in the 21st century.

But data is often onerous to obtain, difficult to trust, and hard to understand. Fixing these problems—making trustworthy, understandable data flow more freely, consistently, and reliably—will provide a wellspring of new ideas and companies to prosecute them.

This post makes a case that there is a structural problem standing in the way freely flowing data and describes a method for removing that structural barrier.

The Long Tail

In October 2004, Chris Anderson introduced the concept of the long tail in an article in Wired magazine. The idea, simply put is that the infinite shelf space and near-zero distribution costs brought about by the Web have revolutionized many businesses by allowing them to compete for business that was formerly too expensive to service.

The concept is called the long tail because if you plot the power law distribution of the relevant data (e.g. revenue from sales of a given book title, song title, airline ticket to a particular destination, and so on) there's always a cut off point where it gets too expensive to service the business using traditional business models. Here's one of the charts from the Wired article:

Notice that in the example shown there is a line on the curve and to the left of that line the words "Songs available at WalMart and Rhapsody". The area under the curve to the left of the cut line is the head of the curve. The area under the curve to the right of the cut—the yellow sections—is the tail and since it's long when you have infinite shelf space, it's the long tail. The area in the long tail is the revenue available to Rhapsody but not to WalMart.

The important point is that Amazon, Rhapsody, and Netflix, to use the examples in the graph, can sell all the same product as their competitors as well as product their competitors can't. A brick and mortar book store can't stock every book, but Amazon can. In many cases the area—and thus the available revenue—of the tail is larger than the area in the head.

The Long Tail of Consumer Credit

In credit markets, the kings of the long tail are Visa and Mastercard. You need credit to make a purchase. Before credit cards, you would have made a deal with the local merchant to extend credit, or in the case of a large purchase, taken out a consumer loan at the bank (my parents used to do this). Now, we just put it on the card.

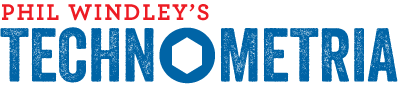

The credit card, largely developed in the 1950s and 1960s represents a huge leap forward in thinking about how credit is extended. Some companies, like Diner's club and American Express developed a credit system that was based on each merchant and consumer having a direct relationship with the credit card company. Many banks did the same thing. In contrast, Visa and the Mastercard established credit networks. The following diagram depicts the relationships in the credit network.

In a credit network, both the customer and merchant have a relationship with their respective bank and their banks have relationships with the Visa network.

| Without Credit Network | With Credit Network | |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship | one-to-one | any-to-any |

| Credit Terms | per-loan | on demand |

| Penetration | select merchants | ubiquitous |

| Processing cost | expensive | cheap |

Table 1 shows a few of the differences between credit before and after credit cards:

- Relationship—before credit networks, credit was extended on a one-to-one basis. You made a credit arrangement with each lender. With credit cards, the arrangement is any-to-any, you can walk into almost any merchant on earth and use credit with no need for a prior relationship. Moreover, in the networked model, both customer and merchant have relationships with independent banks. Any bank will do, so long as they're a member of the network.

- Credit terms—before credit networks, credit was done on a per-loan basis. When you needed credit, you filled out the forms for a particular credit transaction. The next week you might do it all again for another. With credit networks, you get credit on demand, in real-time

- Penetration—before credit networks, you had to select merchants based on what cards they accepted. This was frustrating to merchants and customers alike. With a credit network, even though there are still many cards, they are interoperable with any merchant, making their penetration nearly ubiquitous.

- Processing cost—without credit networks each transaction has to be negotiated and approved individually and, often manually. With a credit network transactions costs are greatly reduced through standardized contracts and automatic approval and settlement.

These attributes are what give credit networks their long tail potential. Credit transactions of all sorts are available to a wider range of people for a wider range of goods and services from a wider range of merchants.

The Credit Network

We call Visa a "network" but that label may be confusing to people who think of networks in terms of routers and data connections. In fact Visa is two things (yes, I'm simplifying a great deal here):

- A collection of contracts

- A protocol

Notice there are no wires. The wires are provided by companies like First Data Corp. who actually do the processing according to the terms of Visa's contracts and protocol. Nevertheless, a network it is because it links countless people and merchants via their banks through the mechanisms of contracts and protocols.

The magic of Visa is the realization that each bank didn't need a contract with every merchant and every customer or even a contract with every other bank. That's why Visa is a "network." Visa has contracts with each bank, the banks have contracts with customers and merchants and the chain of contracts from a customer, to her bank, to Visa, to another bank, and finally to the merchant is sufficient to convince the merchant that she will be paid when she walks in a buy a new pair of shoes. Every time you use your credit card, you exercise a different path through those chains of trust. Visa is thus a trust framework.

By establishing a network that was

- any-to-any,

- on demand,

- ubiquitous, and

- cheap,

Visa was able to create a system that services the long tail of credit. Almost any transaction, almost anywhere can be handled by their network for pennies on the dollar.

Data Exchange Networks

The world of data exchange looks, in many ways, like the world of credit before Visa. Companies like Acxiom, D&B, Experian, and Lexis-Nexis sell data on a one-to-one basis, according to pre-executed contracts, in batch. And it's not cheap. These are companies who have built profitable businesses servicing the head of the curve. But they don't service the long tail. They can't, because they don't have a network.

Imagine you want to start a business that needs access to risk data (i.e. data about the trustworthiness of a business or person). First, you'll have to go through the sales process where you'll be screened to ensure you can sign a contract that has a monthly minimum (say $5000/month), then you'll have to go through legal to get contracts in place, finally you'll agree to the format for your batch of data and integrate your systems with those of the data company. Of course, you'll pay more if you need data more frequently than the norm.

If you only need a little data, or data on demand, or from different sources depending on the transaction, you don't fit in the head of the curve. How many startups don't get built because their business model needs, but can't afford, access to data? How many startups don't get built because they can't make data available cheaply? These are lost opportunities that need a new model if they're to be realized.

A data network solves this problem in exactly the same way that the Visa network solves the credit problem. By putting contracts in place up front and building a trust framework upon those contracts, a data network allows cheap, ubiquitous, on demand, any-to-any access to data.

Drummond Reed has built a company around this very idea, called Respect Network Corp (RNC). The idea is that like Visa or Mastercard, RNC will use standardized contracts to create relationships with data providers and data consumers. Protocols will describe how data transactions are initiated, negotiated, and consummated. Payment will be based on the value of the data but is likely made outside the data network on an existing payment network since they're optimized for that. As an aside, if you look at RNC's business model, you'll see a slightly different version of this based not on raw data transfers as I've described here, but more long-term relationships between merchants and their customers.

Kynetx is working closely with RNC in building the network. The model and legal framework are fairly well understood. What is less well defined at this point is the nature of the data exchange protocols. Our recent white paper, From Personal Computers to Personal Clouds, outlines what we think the nodes in the network will be like. The network itself must provide services to these nodes so that they can interact efficiently and safely. Specifically, the network must provide the following services:

- Reputation—in any-to-any interactions, players will frequently do business with nodes in the network with whom they don't have a pre-existing relationship. In the credit network, this function is performed by the banks who issue merchant accounts and by fraud algorithms that try to detect bad actors. In a data network, anyone, even the customer, might be a data provider, so a reputation system can remove some of the risk in knowing who is providing reliable data.

- Discovery—finding the data provider who has the data you want at a price you're willing to pay is tough job without some help. The network will provide discovery services to aid in this task.

- Semantic Mapping—the individual nodes in the network provide semantic data interchange, but for that to work, they need semantic maps (e.g. ontologies) that have been agreed to by participants in the network.

- Brokerage—the network facilitates payment, probably through an existing credit network. The network also facilitates setting up subscriptions to data services by passing channel details from publisher to subscriber when the relationship is established.

Building this network is a tall order compared to building credit networks. Financial transactions, for example, have simple semantics compared to data transactions. A few well-established protocols suffice for authorizing and settling credit transactions. In contrast, data transactions may need multiple protocols depending on the exact exchange, even with semantic data interchange in place. Nevertheless, such a network would open up the long tail of data transactions for dozens, even hundreds of companies in the same way that the Web opened up the long tail to ecommerce companies.

The good news is that in the second decade of the 21st century, we're ready to take on this task. The Web provides a foundation for transport and recent advances in the understanding of APIs and data interchange have prepared countless developers and companies to work in this new world. The technologies and systems described in From Personal Computers to Personal Clouds including the Event eXchange Protocol (EXP), Kinetic Rule Language (KRL), and XRI Data Interchange (XDI) are the key components in building this network. The legal framework being put in place by Respect Network Corp provides the glue that binds them together.

Public and Private

There may be some reading this who have grave misgivings about what I've described because it envisions a private, rather than public, data network. I believe that this network has to be, at least partially, private for the same reasons that no one has ever created a public credit network to rival Visa and Mastercard. The primary reason is trust.

The protocols that underlie the network I've described are all public or open source and thus available to anyone. What can't be open source is the legal framework that engenders that trust. There will necessarily be an organization that is the foundation of those contracts. While there may be several of these data interchange networks over the next few years, I believe this will likely devolve to duopoly as most other quasi-public utilities seem to do.

Unlocking Data Interchange

The network I've described in this paper solves a structural problem in data interchange that limits current business models to one-to-one, heavyweight relationships. Building an open data interchange network underneath a trust umbrella, enables new business models to thrive by reducing the friction and expense through lightweight, any-to-any interactions.