Summary

If we're to build personal clouds supported by a cloud operating system (COS), then we need to understand the key services that the COS would provide to the user. Operating systems are not monolithic pieces of software, but rather interlocking collections of services. One of the most important things to figure out is how a cloud OS can mediate an integrated experience with respect to authorized access to distributed online resources.

If we're to build personal clouds supported by a cloud operating system (COS), then we need to understand the key services that the COS would provide to the user. Operating systems are not monolithic pieces of software, but rather interlocking collections of services. One of the most important things to figure out is how a cloud OS can mediate an integrated experience with respect to authorized access to distributed online resources.

The concept of identity is foundational in modern operating systems. In Linux, for example, user IDs (uid) and group IDs (gid) are used by the kernel to determine file and device access as well as process ownership and control. User names and passwords are just the means of reliably setting the user ID so that the kernel can determine access levels.

From this simple, foundational identity system and its associated access control mechanisms grows a whole virtual world that you think of as "your computer." When you log into a machine, you are presented with an environment that makes sense of your files and your programs. You control them. They're arranged how you like them. The system runs programs just for you. You're work environment is highly personalized.

We don't see this same kind of integrated, virtual experience when we're online because there's no foundational concept of identity online. We struggle to provide context between different Web sites. Numerous standards from OpenID to OAuth have been developed to bridge these gaps, and we've come a long way, but they are not enough—not yet. In short, people have lots of identifiers on multiple Web sites, but they have no overarching identity context, no presence. Bridging these various systems to provide integrated access control has been one of the most important areas of technology development over the last five years.

One of the interesting developments in access control for distributed online resources is a project called User Managed Access or UMA. For purposes of this blog post I'm going to simplify it—and OAuth—a great deal, so if your an identity expert, bear with me. UMA extends the ideas behind OAuth in several key ways. The one I want to focus on is its introduction of a critical component that provides the overarching authorization context we need in a cloud OS.

I would misconstrue UMA and OAuth if I were to compare them too closely to the identity and access control systems in Linux. The online world is vastly more complicated because it is distributed rather than centralized with myriad identity systems and methods for controlling access. Recently OAuth has had great success in creating a standard way to control access to APIs. I credit OAuth with much of the success APIs have had over the last several years. Still OAuth suffers from some limitations that I think keep it from playing the role we want in a cloud OS.

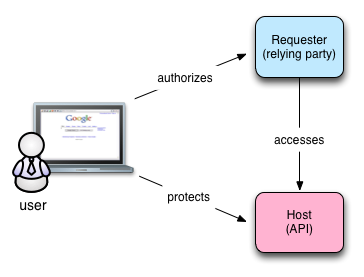

To see why, let's look more closely at OAuth. You've undoubtedly used OAuth to link services on one Web site with another. That's its primary use case: Site A, the "requester" wants access to a resource being hosted on Site B—usually behind an API. The requester needs your authorization to access the resource. You get redirected to the host where you're asked if you approve. If you grant access, a relationship is hardwired between the host and the requester. You can revoke the access at any time at the host. The picture looks something like this:

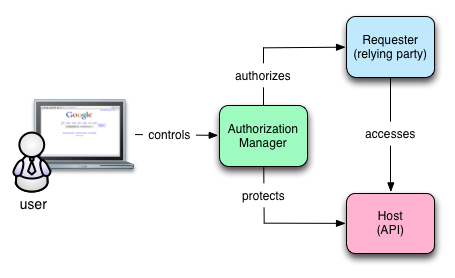

In contrast, UMA provides another critical piece that acts on behalf of the user called the authorization manager. Consider the following picture:

The only difference in these two diagrams is the authorization manager. In the UMA diagram, the user controls the authorization manager and it interacts with the requester and the host. The authorization manager represents the user in the authorization transaction and its subsequent management. Think about all the places you've used OAuth. Can you remember them all? Would you know you had to sever a connection between Facebook and Twitter if you wanted to stop some obscure status update behavior? Maybe not.

In the OAuth diagram, no system represents the user's interests. Instead, the user is responsible for bridging the context between the sites as well as remembering what's been authorized and where. With UMA's authorization manager, the user has one place to manage these kinds of interactions.

An authorization manager of some sort will be a key component in a COS. The authorization manager is active, rather than passive. The authorization manager contains policies that allow it to act as the user's agent, even when the user isn't present. Rather than a single, hardwired connection, the authorization manager can be continually consulted and access can be granted or denied based on changing conditions and contexts.

Don't make the mistake of thinking this is just about identity. In fact, it's not really about identifiers and associated attributes at all. It's about permissioned access to distributed resources. We don't have to unify identifier systems—although we may need to abstract them—to achieve our purpose. One of the key features of UMA is it's ability to offer fine-grained access control to any online resource—not just APIs—regardless of the underlying identity systems and their credentials. For a complete discussion of how UMA, OAuth and OpenID Connect are related and where they differ, I recommend this blog post from Eve Maler, the force behind UMA.

Regardless, when I contemplate an UMA mediated experience from the user's perspective, I think they'll view UMA as providing a personal context to their online interactions. They'll view that personal context growing out of themselves because something knitted their various, fractured online identities together. The same real-world person will be at the heart of all this regardless of the various fractured credentialing and permissioning systems that underlie it.

UMA and its provision for an authorization manager is exactly the kind of development that highlights what kinds of utility a cloud OS provides. UMA is just one example of where people are starting to realize that users need systems that act on their behalf to help them manage their interactions. People need systems in the cloud that represent them and what they want done. Having Web sites and APIs is not sufficient. A cloud OS goes beyond mere hosting to a system of autonomous agents acting against policy to represent people in the cloud.

Of course tackling authorized access to online resources is only the first step. Our interest is in using these systems to control online data and programs so that the user effectively has a virtual online presence that represents her, manages her data regardless of where it may be stored and provides real leverage, so they can get more done with less effort, risk, and cost. The next post in this series will show the role data abstraction plays in this experience.